This article in City Lab examines the explosion in the growth of Malls and their construction in the last decade. The writer begins by stating how 25 percent of the roughly 1,100 shopping malls still alive in the U.S. are projected to close by 2022.

https://www.citylab.com/design/2017/11/the-triumph-of-the-latin-american-mall/546725/

Nolan writes,

“Developers haven’t built a new mall since 2006 (except for one in the bizarre land of Sarasota, Florida). “

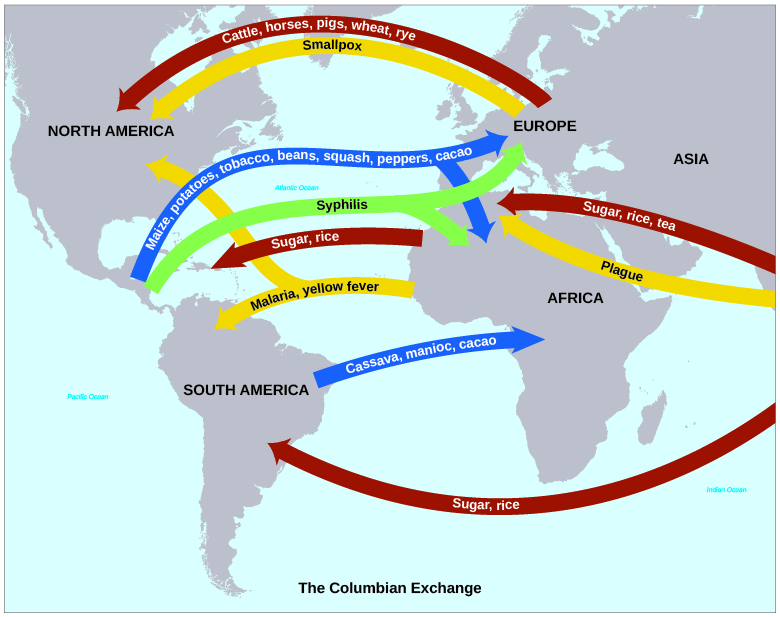

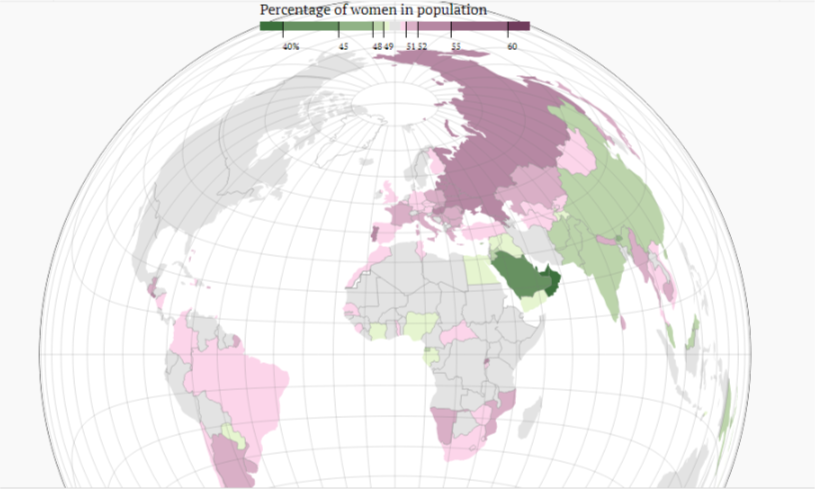

Conversely, 100 new malls were built in Latin America in 2016 alone and, the largest mall in the western hemisphere is in Panama. Nolan describes this trend with an air of wistfulness for a time past.

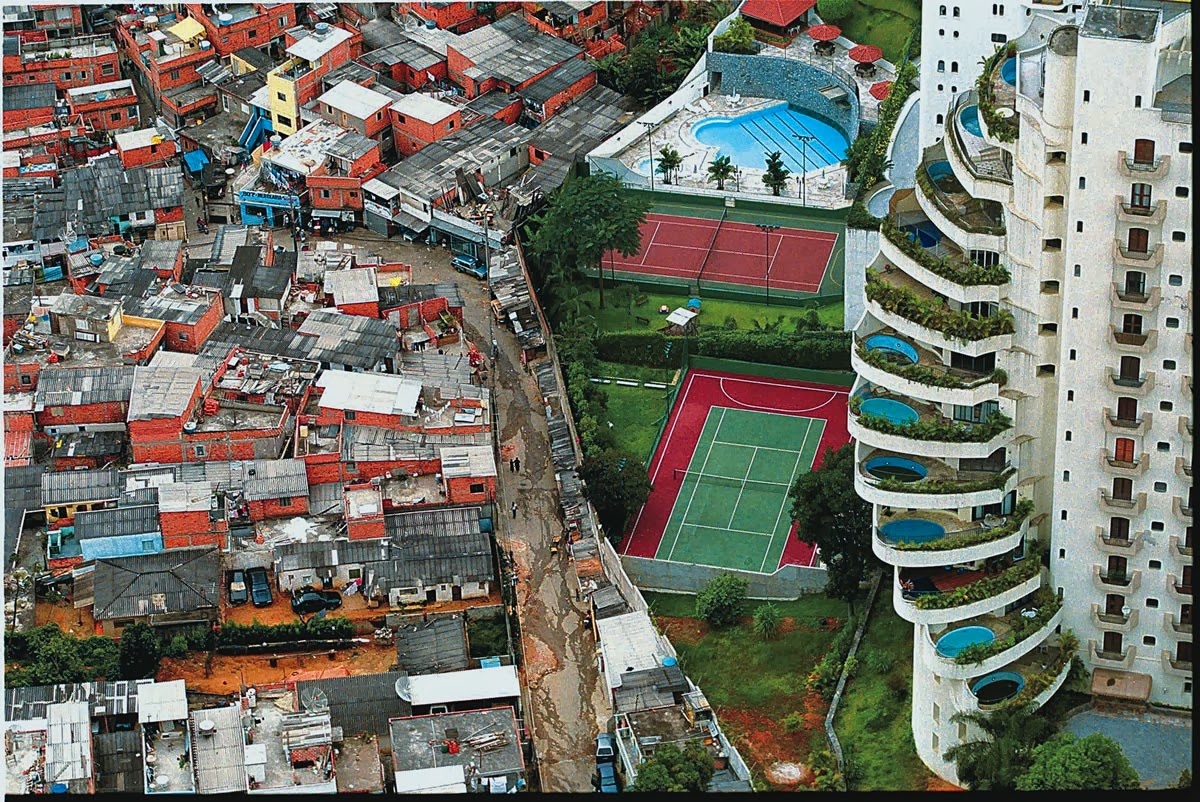

Multiple anchors. Many different stores that attract customers and allow the businesses to benefit from each other’s presence by agglomeration. Beyond retail, Latin American malls often house other major employers, including call centers, healthcare facilities, and office space. The writer describes how he thinks malls as they exist in Latin America today, embody their original designer’s vision of them: mixed-use hubs rather than gigantic shopping hubs. He describes how these malls in Latin America are increasingly incorporating residential homes as well in apartments and condos. The writer argues that is this diversity of use that will allow malls in Latin America to outlive and out-function their North American counterparts.

While these malls in Latin America thrive on diversity and multipurpose usage, they also exist in much more specialized areas and for functions. Nolan describes how there are malls in some parts of Latin America such as Guatemala that exist specifically for dining and restaurants. He also explains how there are malls that exist specifically for interior design and how such malls, not meant for selling clothes, remain rare in the US, and Canada.

American malls are anchored by big chain stores, like Macy’s and J C Penney, and as these companies have gone out of business in recent years, they have dragged the malls built around them down with them. Nolan describes the cultural and social effects malls have had in America especially in the 80s and 90s, at their peak, and in Latin America now. Nolan examines how young people mill around malls and don the fashionable clothing brands and labels as a product of these malls, and how in the wake of stagnating incomes, and a reduction in wage increases, people have less and less disposable income and therefore less and less money to spend in shopping malls.

Nolan describes how the poor internet access and delivery services protect brick and mortar stores from the convenience and ubiquity of online shopping in Latin America. Whereas in North America, malls are doomed because of the ubiquity of the internet, in Latin America, malls remain thriving and abundant because internet access is much less ubiquitous there. It is interesting then that industrialists and capitalists identify this market opportunity and exploit the lack of internet rather than address it. Nolan also cites the security of malls as compared to isolated stores as a reason why people migrate and become concentrated around them. Shoppers also prefer to do their shopping in a safe area. This has led to the rise of the shopping mall in Latin America.

Nolan describes how when we feel nostalgia for malls, maybe what we’re really feeling is nostalgia for a time when incomes were rising in North America, and the quality of life of average people was improving. Today, that’s what’s happening in much of Latin America. But as their mall era begins, and the American one fades, he encourages land developers and people in North America to find a more enduring model for the shopping mall.

I find it interesting how Nolan correlates economic phenomena like the growing middle class in Latin America with less economic phenomena like the activities of children and teenagers to paint a vivid and relatable image of the shopping mall and the impact it has had on society and our daily lives.